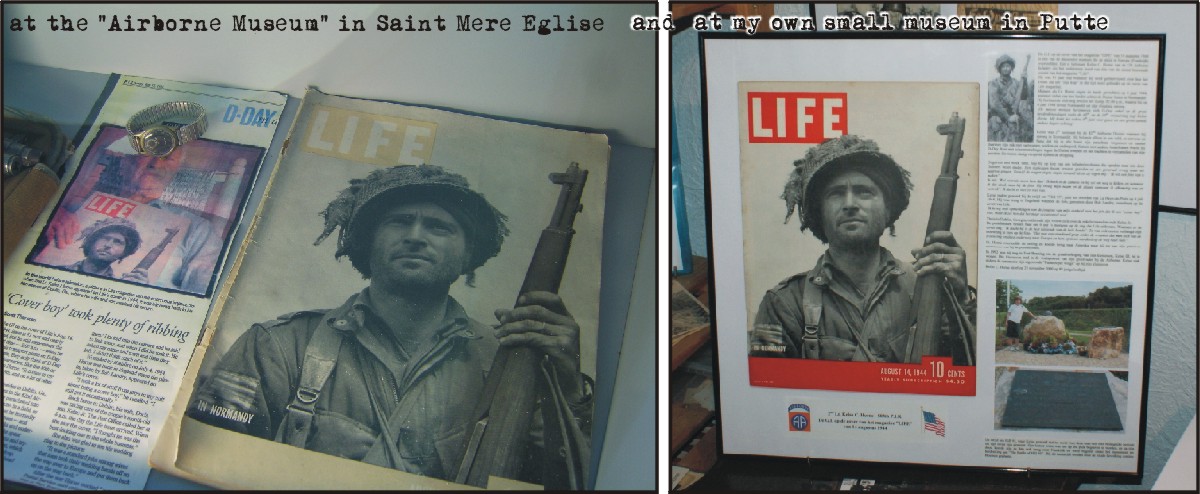

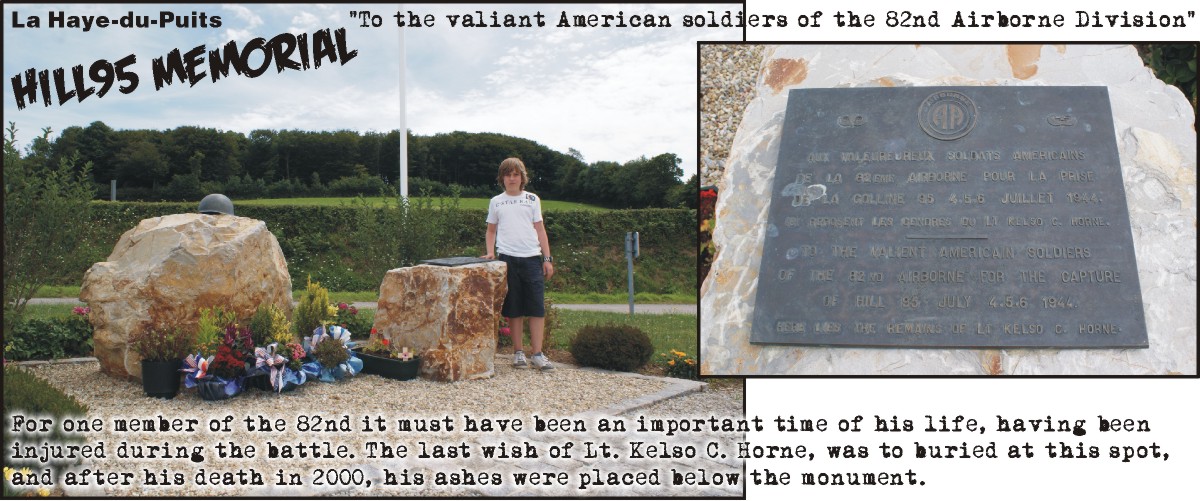

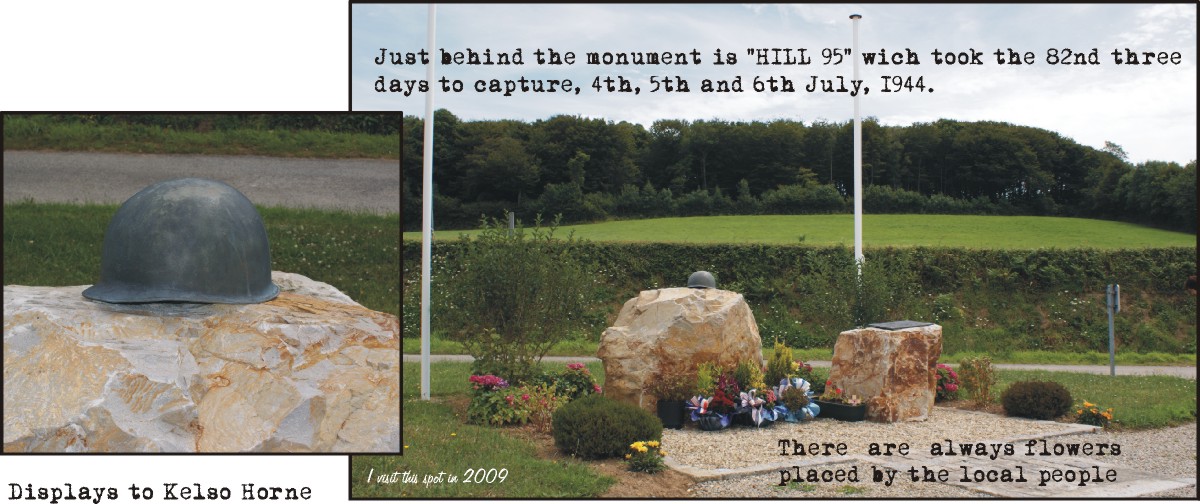

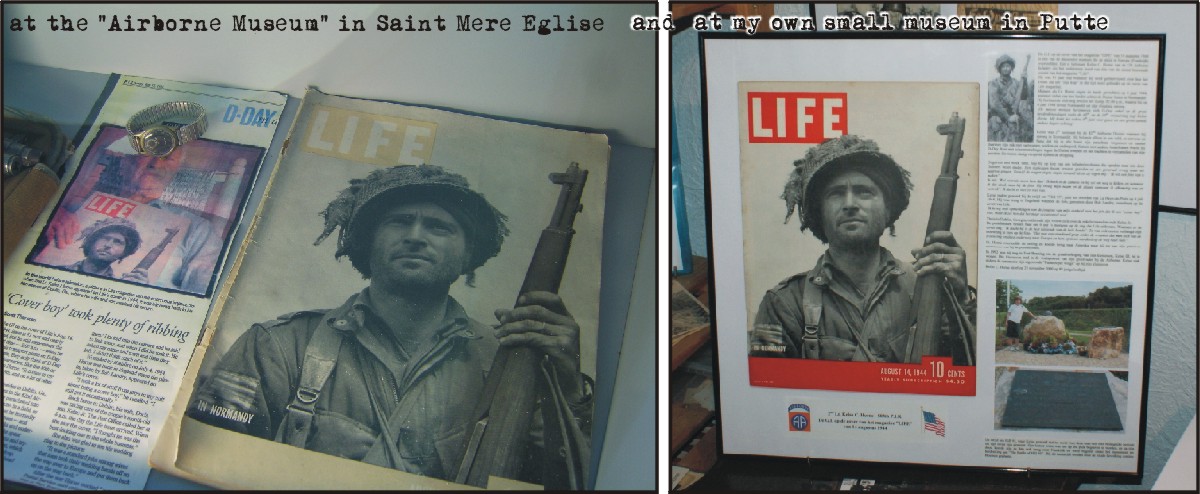

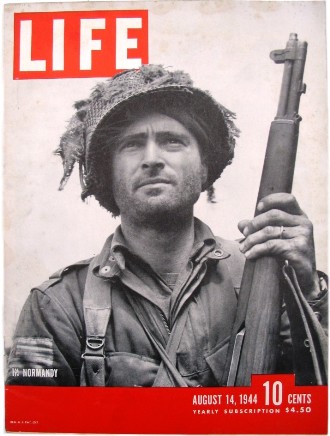

LIFE MAGAZINE AUGUST 14, 1944

This is probably "THE" best known wartime LIFE magazine COVER photo ever. The tough, haggard man on the cover is one of thousands who are winning the battle for France. He is Lt. Kelso C. Horne, platoon leader of 1st Platoon, I Company, 508 PIR in Normandy. Men like Lieut. Horne saw their hardest fighting on June 6, when many of them were landed behind German lines in Normandy with parachute troops. In the great break-through in France, airborne troops are probably being used as infantry shock troops.

This is probably "THE" best known wartime LIFE magazine COVER photo ever. The tough, haggard man on the cover is one of thousands who are winning the battle for France. He is Lt. Kelso C. Horne, platoon leader of 1st Platoon, I Company, 508 PIR in Normandy. Men like Lieut. Horne saw their hardest fighting on June 6, when many of them were landed behind German lines in Normandy with parachute troops. In the great break-through in France, airborne troops are probably being used as infantry shock troops.

The G.I. On The Cover of Life Magazine, August 14th 1944, was 81 years old when he was Interviewed about how he became the face on that issue of Life Magazine at that time.

Kelso Horne never claimed to be a hero. He said, "I didn’t do anything heroic," which is a typical response from a hero. A photograph of the face of Kelso Horne appeared on the cover of "Life" magazine on August 14, 1944. The picture is known to some as "the face," not the face of Kelso Horne, but the face of the infantryman of the American Army. In fact, when the editors of "Time" magazine published an issue on the history of the 20th Century, the picture of Horne’s face was chosen to represent the millions of American servicemen who served their country in World War II and saved the world from Nazi imperialism.

Kelso Crowder Horne, the third child of Josiah H. Horne and Maude Crowder Horne, was born on November 12, 1912. When World War II began in 1941, Kelso didn’t wait to be drafted. He wanted to see some action, "not something just anybody could do," Horne said. As a boy, Kelso had seen air shows in Dublin. "They had people jumping out of airplanes," Kelso remembered. Kelso joined the U.S. Army in June of 1942 in Macon, Georgia. He was assigned to Camp Wheeler for basic training for thirteen weeks. Kelso remained adamant in his desire to be a paratrooper. After four weeks of training in an NCO school, Horne was shipped down Highway 80 to Fort Benning in Columbus.

In February of 1943, Kelso Horne, became 2nd Lt. Kelso Horne. He immediately applied for entrance into jump school. Horne and the other candidates were taken out for a field demonstration. A rocket carrying a dummy paratrooper was fired into the air. As it fell to the Earth, the mannequin was riddled with machine gun fire. "That’s what can happen to you. Now, how many of you want to change your mind?," the instructor inquired. Kelso stood firm in his desire and completed jump school at Benning.

In February of 1943, Kelso Horne, became 2nd Lt. Kelso Horne. He immediately applied for entrance into jump school. Horne and the other candidates were taken out for a field demonstration. A rocket carrying a dummy paratrooper was fired into the air. As it fell to the Earth, the mannequin was riddled with machine gun fire. "That’s what can happen to you. Now, how many of you want to change your mind?," the instructor inquired. Kelso stood firm in his desire and completed jump school at Benning.

Horne was assigned to the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment in March of 1943. After reporting to the regimental commander, Kelso was placed in the 1st platoon of Co. I, 3rd, Bn.. He trained at Camp Mackall, N.C. and Lebanon, Tenn. until Dec. 20, 1943, when the regiment assembled at Camp Shanks, NY. Camp Shanks which was located less than an hour from Broadway in New York City. After three days of administrative duties and learning how to abandon ship, Kelso and his buddies were given an evening pass into New York for one last fling. The 508th spent that Christmas day in camp. Their next Christmas would be spent right smack dab in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge. The regiment boarded the U.S. AT Parker for a 12 day trip to Belfast, Ireland. Two months later, the 508th sailed to Scotland for even more training.

The men knew that they were training for an invasion of Europe, but they didn’t know when or where. As the hour of D-Day approached, Kelso and the rest of the regiment was told that their destination would be eight to ten miles inland from the eastern coast of the Cotentin Peninsula west of St. Mere Eglise, France. The 3rd Bn.’s mission was to organize a defensive sector and the join with the 4th Infantry Division, which would be staging an amphibious landing on Utah Beach. As the skies began to darken on the 5th of June, 1944, final preparations were being made. Equipment checks went on until the last minute. The men ate one last meal, a least for many of them it would a last meal. After downing a few more cups of coffee and a couple doughnuts, the men took the smut from the kitchen stoves, blackening their faces for the nighttime jump. At 2:06 a.m. on the morning of June 6, 1944, Kelso Horne moved to the door of the C-41, which was flying through a dark and moonless night. Just as Kelso saw the waves breaking on the Normandy shore, the green jump light came on. Men began yelling "go!" Kelso waited; it wasn’t time to go just yet. When Kelso spotted the Merderet River and the railroad, he jumped, landing between the two landmarks, just where he was supposed to be.

The C-41s were drifting away from each other. Night flying formations were tough, even for experienced pilots. Most of the eight hundred and twenty pilots flying into Normandy had never flown at night. Some were shot down. Bob Mathias of 2nd Platoon, Co. E, was standing in the doorway when he was struck by an artillery fragment. Despite his wounds, Mathias jumped. He died before he reached the ground. Historian Stephen Ambrose credits Mathias as being the first casualty of the invasion and being the oldest paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division. Kelso, at 31 years of age, was three years older than Mathias. He believed he was the second oldest paratrooper in the 82nd. Most of the men who jumped that night were less than twenty years old.

Kelso found that he was in a small field about a mile from St. Mere Eglise. He found it difficult to get out of his harness. It wouldn’t unsnap or cut with a knife. After a few moments, Kelso calmed down and managed to escape from his harness. As he was heading for the woods, Lt. Horne realized that he had left his field bag behind. Just as he retrieved his bag, Kelso noticed a figure of a man approaching him. He put one round in the chamber of his rifle. Kelso spoke first when the man was twenty feet away. The man, who turned out to be the messenger of the company commander, gave the correct response to Kelso’s challenge. The two men crawled into a ditch to determine their position. Just after another man approached them, the green signal flare went up, signaling the 3rd Battalion to move to the assembly area.

The battalion rendezvoused at a farm house surrounded by an orchard of apple trees. When Kelso got into the house, he went over to put a cup of water by the fire to make himself a cup of coffee. The building became the headquarters of Gen. Matthew Ridgeway. Lt. Horne and his fellow lieutenants gathered up as many men of the 508th as they could find. They took their men to the Merderet River Bridge at La Fiere Manor.

Col. Lindquist, the 508th’s commander, sent Kelso and fifteen to twenty men down the road to clear out a farm house from which the Germans had been firing on the American troops. The squad ran down a sunken lane toward the two-story house. The corpses of four or five German soldiers were strewn around the outside of the house. While the Germans inside the house were distracted by fire from the sunken road, Horne and a sergeant moved into the first floor of the house. The sergeant sprayed the rooms and the ceiling with machine gun fire. A dozen or so Germans came down the steps and surrendered. In the excitement of the moment, Kelso once again left his field bag behind. Ordinarily the bag could be replaced, but a Bible which had been a gift from his wife Doris was in the bag. Kelso never found the bag or his Bible. Kelso noticed that a group of G.I.s were trying to cross the river. The Germans began firing at them. Kelso yelled out in vain trying to warn his buddies, but to no avail. "Not a one of them, as far as I know, made it all the way across," Kelso remembered.

Kelso picked up an M-1 rifle . It had belonged to a major, who had the fatal misfortune of being ambushed in a fake surrender trick by the Germans. With only an hour of rest, Kelso and his men were suddenly subjected to intense artillery fire. Col. Lindquist gave orders for the men to run, in order, to headquarters. They made it to the railroad track and then to the bridge at Chef du Pont, where they remained for the rest of D-Day.

The next day, General Gavin led his forces toward the command point, yelling "Come on! Let’s go! Nobody lives forever!" Horne remembered very little after D-Day plus one until Independence Day. He was tired. The daily fighting and expectations of combat at any time allowed no time for keeping a diary. He did remember the capture of 1820 German soldiers by his troops and those of the 90th division near Cherbourg. After things began to calm down, Lt. Horne was relieved to learn that all of the men in his platoon had made it that far without casualty - a lucky streak which wouldn’t last too much longer.

When Kelso crossed the La Fiere Causeway, he came upon a group of dead German soldiers lying in a ditch. He was standing astride what he thought was a dead soldier. The man, only dazed and not dead, spoke to Horne, yelling "Komrade! Komrade!" Despite the urging of some of the men, Horne refused to shoot the helpless man. Only a few moments later after Horne had left the scene, an inflamed young soldier came across the road. He machine gunned the German to death. "That happened a lot," Kelso remembered.

About a week after the invasion, Kelso and his platoon from Co. I were walking down a road toward a French town. Gen. Lawton Collins, commanding the 7th Corps, drove up along the column and asked to speak to the officer in command. Horne advised the General that there were Germans in the town because they had firing on our troops earlier in the day. Collins, owing to the fact that discretion is the better part of valor, ordered the driver to turn the staff car around. Before the car left, Bob Landry, a photographer for "Life" magazine asked permission to take a picture of Kelso Horne. Landry instructed Horne to kneel down and look off in the distance. Horne complied and thought not much more about the snapshot. Horne had mentioned it to his wife Doris in his letters. The photograph was selected by the editors of the magazine to grace the cover of the August 14th issue. Horne’s family and everyone in Laurens County were elated.

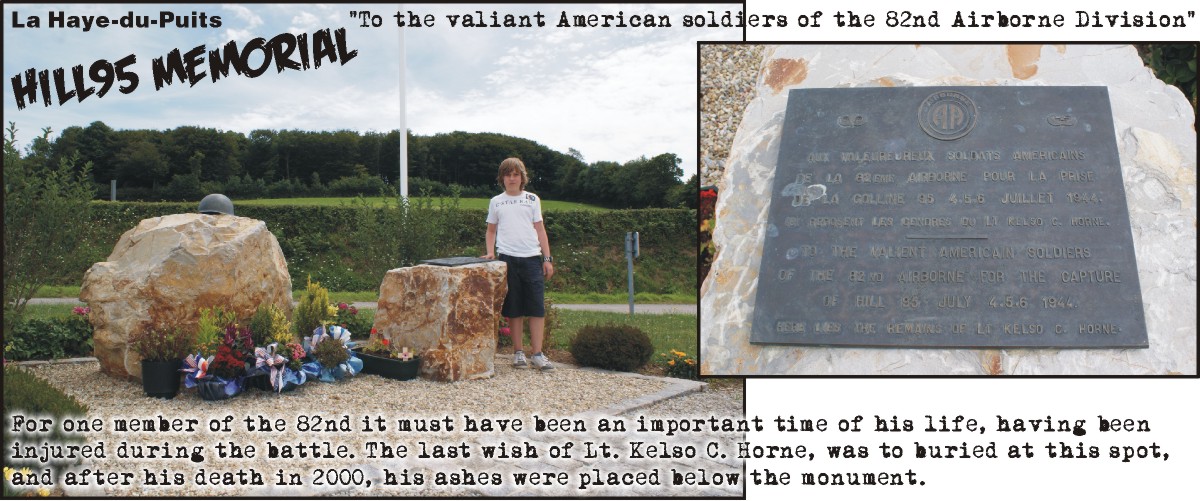

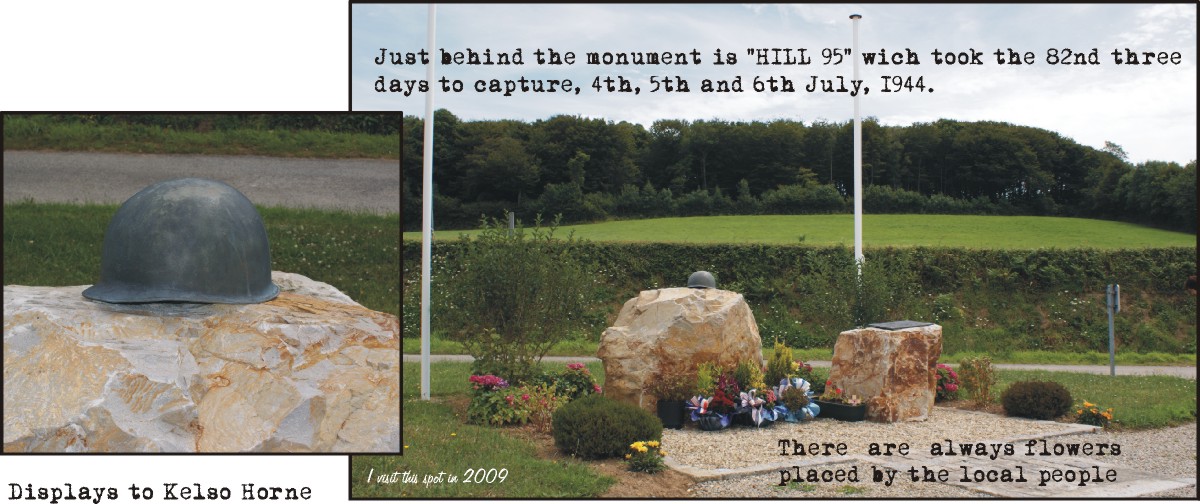

As Independence Day approached, the 508th was moving north of La Haye-du-Puits. Their objective, Hill 95. Horne and his men knew the Germans were up there on the hill. They heard them talking during the night. Early on the morning of July 4th, Lt. Horne was giving his daily report to Sgt. Raymond Conrad, 1st Sergeant of Co. I. While listing those who had been killed and wounded, a round pierced Conrad’s body from one side all the through to the other. Kelso was terribly shaken. The two men had gone through basic training together and were close friends. A little while later, Lt. Horne was walking with his messenger, when the young man was hit in both legs with machine gun fire. Once again, Kelso had narrowly escaped being shot. Things were getting worse. One of the company mortar men and the platoon sergeant were severely wounded.

Kelso began to question the prudence of the decision to attack the hill. Col. Mendez was adamant. Lt. Horne knew that the land approaching Hill 95 had no cover, not even a rock to hide behind. Col. Mendez grew angry when Kelso intimated that the colonel would be safe in the rear behind the rocks, while he and his men would be in untenable danger. The attack went off just as planned at eleven o’clock in the morning, five minutes after the artillery barrage began. Lt. Horne was ten feet out of the hedgerow when he felt something. "I never heard the shell. I know it was a shell, because it was a fragment that hit me. It just felt like somebody hit me in the chest with a baseball bat. It knocked me down and when I got up my pistol had fallen out of its holder," Kelso told his biographer, Perry Knight. Pat Collins, who was standing beside Horne, took a hit and fell. Horne told Collins that he had been hit in the arm. Collins looked over at Horne and said, "You’re hit, too! You’ve got a hole in your jump suit. You got it bad," Collins said. Horne noticed he was bleeding and moved back to the security of the hedge. He disassembled his rifle, threw the parts in different directions, and began to move back toward the rear. Horne noticed that he had left his pistol at the point where he had been shot. He crawled back to the spot, picked his pistol up, and then had the strength to walk back to the rear field hospital. Horne was sent to a hospital in Cheltonham, England, where he arrived a couple of days later. The attack fizzled that day, but the regiment took the hill the next morning after the Germans had abandoned it on the night of the 4th.

Kelso remained in Cheltonham until the early days of August. One day while he was lying in the bed, the man in the next bed said, "You’ve got a boy!" Horne was momentarily puzzled. He knew that his wife Doris, the former Miss Doris Garner, was expecting a child, but didn’t know how the man would know about it. Doris had tried to get word to Kelso through the Red Cross. Horne’s uncle, Frank Cochran, knew about the slowness of sending a message to a soldier overseas. He sent the announcement to the military newspaper, "Stars and Stripes." The July 25th edition of the paper carried the news of the birth of Kelso’s son, Kelso C. "Casey," Horne, Jr. who had been born on July 18th. Casey joined the U.S. Army like his father. Today he practices law in Dahlonega, Georgia. Kelso C. Horne, III became a third generation paratrooper in the mid 1990s. At the awards ceremony at the end of jump school, Kelso C. Horne, III had his wings pinned on him by his grandfather. They weren’t a new pair of wings. They were the same wings that had been pinned on Kelso, Sr. in 1943. Pride and tears overflowed that day.

From Cheltonham, Horne was sent to Wales for further rehabilitation. Horne returned to the 508th the day the unit left with the 82nd Airborne Division for a jump in Holland. Unable to return to duty, Horne remained behind with orders to help care for the wounded until the unit’s return. Horne remained with the 508th throughout the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944. On Valentine’s Day, 1945, Kelso returned to the states. He was sent to Finney Hospital in Thomasville, Georgia - close to home, but not close enough. Kelso was sent even further away from home, this time to Miami, Florida. He returned to duty as a training officer at Fort Benning, where he was discharged in October, 1945.

Kelso and Doris returned to Dublin to make their home. Kelso continued to serve his country with the United States Postal Service. He died on a Saturday, the Saturday after Thanksgiving. In this holiday season, more than fifty years later, let us give thanks for men like Kelso Horne, the man behind the face, and all of the men who risked their lives for to preserve the freedoms we enjoy today.